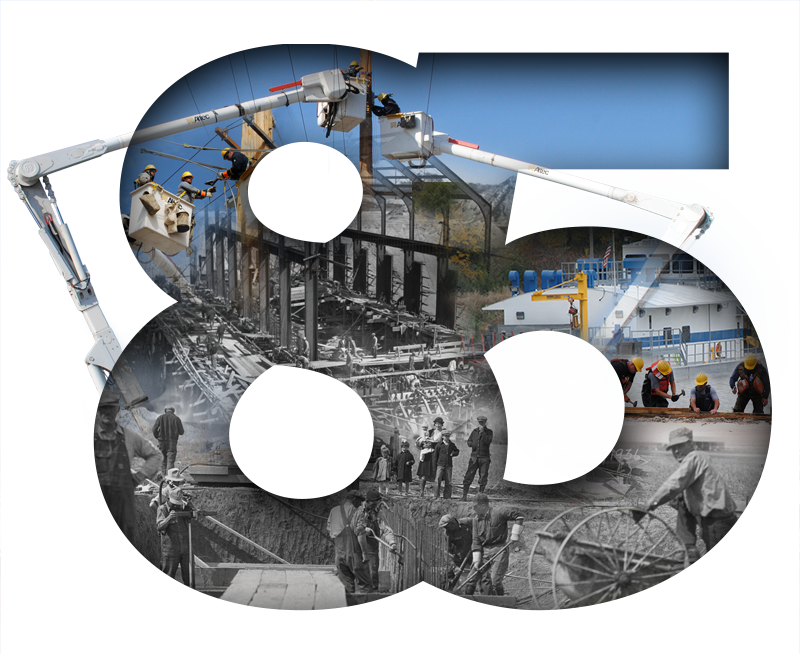

Loup Power District was the first public power district in Nebraska.

In the midst of the Great Depression, word came to Columbus that the Public Works Administration awarded $7.3 million to Loup Power for construction of a power canal.

“Happy days are here,” announced the Columbus Daily Telegram on Nov. 15, 1933. It was indeed a happy day for a group of Columbus businessmen who had worked for months on the plan. They wanted to reverse the effects of the Depression and provide a power source at the same time.