An Electric American Adventure

— Originally published in the Summer 2022 issue of The Generator.

Jack Smith pushed a skateboard across America four times. Then he rode an electric skateboard from Oregon to Washington, D.C.

That might be enough adventure for most people. But Smith isn’t like most people.

“I’ve been attracted to crossing the country in different ways,” he said.

In early June 2022, Loup Power District employees saw a vintage Volkswagen van pull up to the electric vehicle charging station in the parking lot. They had to investigate. This was indeed “different.”

And so, we met Smith and his childhood friend, Larry Newland, and asked them to share their stories.

HORATIO’S DRIVE

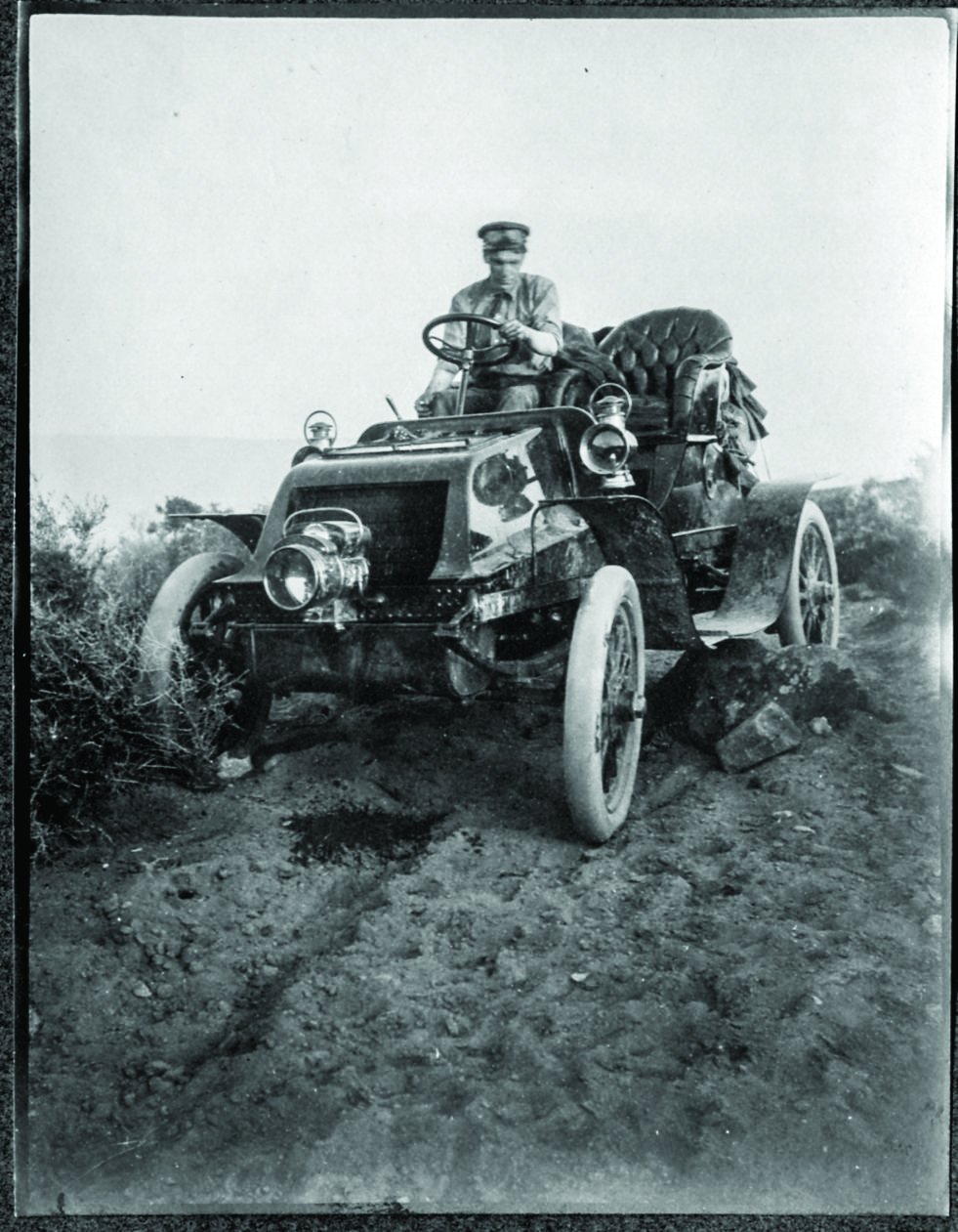

In 2021, Smith sat down to watch the Ken Burns documentary “Horatio’s Drive” at his home in California. It tells the story of Dr. Horatio Nelson Jackson. He was at San Francisco’s University Club in May 1903 when he made a $50 bet (equivalent to more than $1,500 today) that he could cross the country in an automobile.

A few days later, he purchased a 20-horsepower Winton touring car. He was 31 years old with very little driving experience and no maps to follow. The country had only 150 miles of paved roads.

Five days after the bet, he took off with Sewall K. Crocker, who served as travel companion, mechanic, and backup driver. A bull terrier named “Bud” joined them in Idaho. He was outfitted with goggles to protect his eyes as he helped watch the road.

Most people doubted that the automobile had a future. But Jackson proved them wrong when he arrived in New York City 63 days later.

Smith was hooked on the story immediately. After he watched the video, he bought a book and delved into the story even more. Then, he decided it wasn’t enough for him to simply read about Horatio’s drive. He wanted to make it.

“I told my wife, ‘I want to retrace this guy’s route, but I don’t want to do it in a regular vehicle.”

SKATEBOARDS ACROSS AMERICA

Most Americans have never traveled across the entire country. Smith has done it multiple times — but never in a “regular vehicle.”

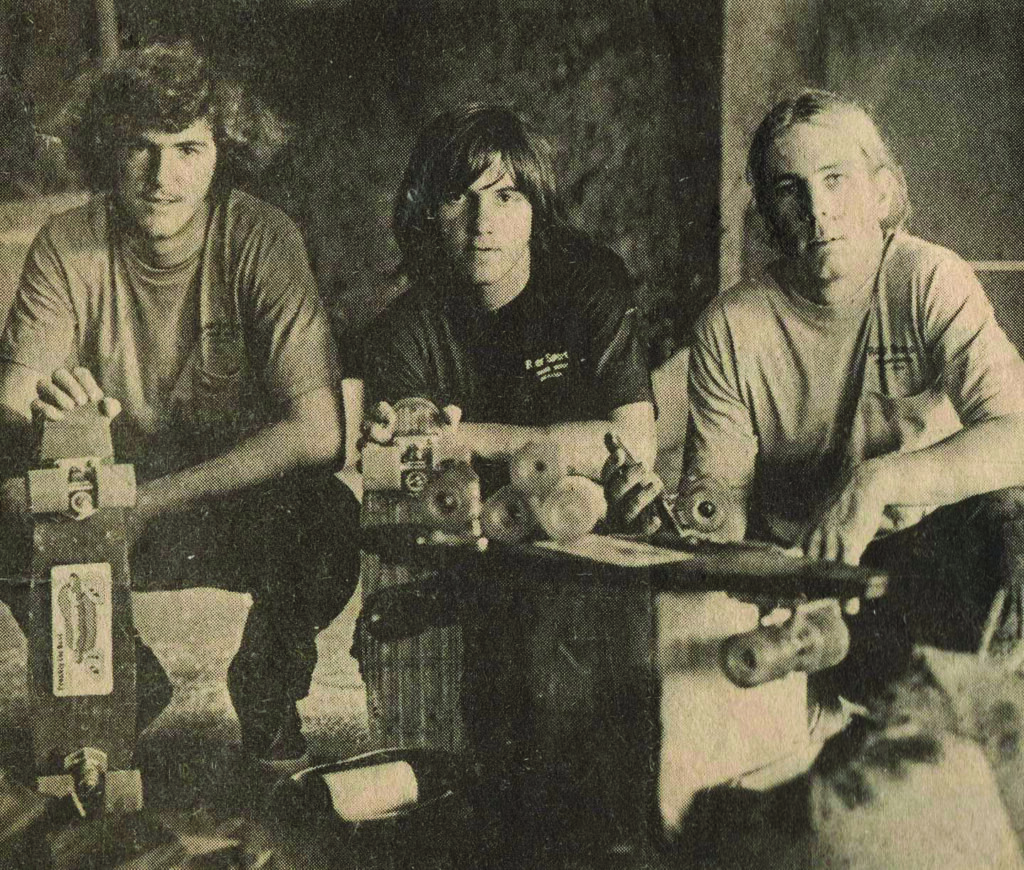

Back in 1976, at 19 years old, he and three friends became the first to skateboard across America, with sponsorship from a company called Roller Sports.

They did so in leapfrog fashion, with each skater going about three miles at a time. In between, the skaters got a ride in their support car — a 1969 Firebird.

Each guy skated a total of 35–50 miles daily, depending on the terrain. As a team, they could travel 150 miles on a good day. The trip from Oregon to Virginia took 32 days.

“It was a great way to see the country,” Smith said. “You’re going so slow, you don’t miss anything.”

If anything, the trip only expanded Smith’s love of skateboarding. He competed in the infamous “Signal Hill Speed Run” in Signal Hill, Calif., held from 1974–78. Participants in the race set world records in skatecars, topping out at almost 60 miles per hour on the hill with a 30-degree drop. The annual event ended when sponsors withdrew because it became too dangerous, with multiple life-threatening crashes.

By 1984, the “new guys” on the skateboarding scene were tired of hearing all Smith’s stories. They wanted stories of their own, and asked if he would consider another cross-country trip. It didn’t take much convincing. The four-man team took on the task again, raising money for Multiple Sclerosis awareness along the way. The journey took 26 days.

In 2003, Smith’s son, Jack, died of complications from Lowe Syndrome, a rare genetic disease. His father died of Alzheimer’s Disease in 2013. Smith made two more cross-country trips to raise funds and awareness for those conditions in the years they died.

That fourth trip in 2003 included his younger son, Dylan. The 3,618-mile journey set a world record that was broken by British skateboarder David Cornthwaite in 2007.

By 2018, Smith was referred to as a “skateboarding legend” by media outlets and his fellow peers.

It might have been enough for most people. But again, Smith isn’t like most people.

That year, he decided it was time for one more trip. But this time, he was going to go solo on an Inboard M1 electric skateboard. The 2,394-mile journey from Eugene, Oregon, to the steps of the Smithsonian Museum took 45 days.

He was 61 years old.

THE RUST BUS

Smith was only three years out from his electrified skateboard trip when he watched “Horatio’s Drive.”

Still, the prospect of another journey was too exciting to ignore. It wasn’t a question of if he’d recreate the trip, but how.

He contacted his friend, Michael Bream, owner of EV West in San Marcos, Calif. Smith wanted to get some input and ideas for this trip. (Read More about Bream HERE)

Bream immediately offered the “Rust Bus,” a 1964 VW van that he converted to run on all-electric power.

At first, Smith was a little skeptical. He was hoping for a Tesla, or maybe the DeLorean that Bream was converting. But it wasn’t ready.

And so, he decided the two-speed bus would have to do. “It’s a very basic vehicle,” Smith said. “Just as Horatio’s was.”

But basic doesn’t quite describe the vehicle, with its contrasting vintage frame and new technology —an electric motor and charging port, and 800 pounds of Tesla batteries. And, Smith realized, that’s just what he was looking for.

On May 4, 2022, he hopped in the rust bus and headed west from San Francisco with friend Mike Adamski. They soon learned they wouldn’t exactly be traveling in comfort. The bus rattled, and leaked, and the ride was often bumpy, despite the upgraded shocks.

They hit cold spring weather and snow on the early part of the journey. Smith wore long underwear and gloves. The cold air snuck in, despite the tape on the windshield and the added foam insulation.

Still, Smith knew he didn’t have it so bad, when he compared his experience to that of Jackson. “Those guys were in an open-cockpit car navigating by compass,” he said.

In contrast, he had navigation equipment, paved roads, modern amenities, and more.

Twenty-one days after leaving California, Smith and Adamski reached New York.

LARRY & THE LINCOLN HIGHWAY

Smith successfully completed Horatio’s drive east. After a short break, it was time to head home.

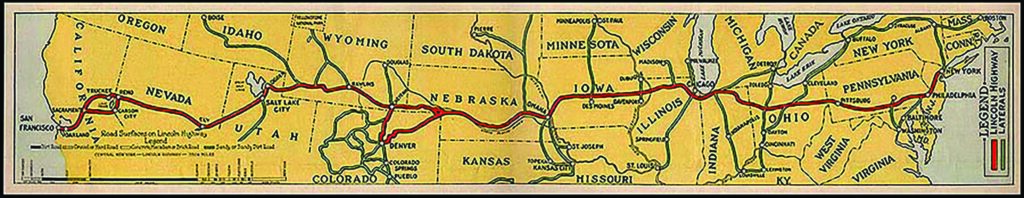

And this time, he was going to follow the Lincoln Highway — the first transcontinental road in the United States.

The highway was dedicated in 1913 and ran from Times Square in New York City to Lincoln Park in San Francisco. Cities and towns along the 3,389-mile route prospered as travelers took to “America’s Main Street.”

The Lincoln Highway was gradually replaced with numbered designations in 1926. Much of the route is now U.S. Highway 30.

Smith took a short break in New York and it was time for Mike Adamski to head home. But he got a new companion for the second leg of the journey — his friend Larry Newland.

Newland was one of the first people Smith met when his family moved to Morro Bay, Calif.

Like Smith, he is lured by adventure. He once walked a portion of the Donner Party route from Reno, Nev., over the Sierra Nevada mountains into Placerville, Calif.

He had planned to be a part of Smith’s 1976 skateboard trip, but backed out because he started a rock band. “Almost 50 years later, here we are on a cross-country trip,” Smith said.

There is no fundraising cause for this trip. “It’s just a fun adventure,” he said.

But their costs were minimal. At night, the pair typically stayed at campgrounds. Smith slept in the bus on top of the batteries, while Newland pitched a tent. They plugged in the bus to charge overnight so they were ready to hit the road by morning.

Along the way, they met a lot of interesting people who were intrigued by the bus and wandered over to take a look — young and old, police officers, construction workers in downtown Manhattan.

“It’s an attention magnet,” Jack said. “First they come up and they’re excited by the bus because they think it’s cool,” he said. “It makes them smile.”

When they found out it was electric, they wanted to see the motor and batteries.

The pair was always willing to show off the bus, talk about their adventures, and answer questions. The most popular question? “How far can you go on a charge?”

FROM A TRICKLE TO A FIRE HYDRANT

Newland kept a log every day of the journey. The top speed of the Rust Bus is about 95 miles per hour. Generally, they took a leisurely pace of about 40–55 miles an hour since they traveled mostly on state highways and some back roads.

He loved that part of the trip. After all, he asked, are you really seeing our country if you’re barreling down the interstate at 70 miles an hour?

They averaged about 20 miles per 10 percent of battery power on their trip west. That equates to about 200 miles per charge in ideal conditions. That range decreased in hilly terrain or windy conditions.

But a 200-mile range is just fine with Newland. After a few hours in the car, he needed a break to stretch his legs and get a cup of coffee or bite to eat.

He believes that is a business model for the future. Imagine charging your car while having coffee with a friend or getting your groceries. Convenience stores could add amenities for EV owners who need to take a break from the road and charge up.

“This trip has helped shape my idea about the viability of electric vehicles,” Newland said.

He’s guessing that in 5 to 10 years, most people will have an electric car that they use for trips to the store, to school, to work. But they will also have a gas-powered pickup or car for their family vacations or home improvement projects.

He knows not everyone sees electric vehicles in such a positive light, but he also witnessed people change their mind after learning about the bus and their trip. Some were shocked at the bus’ instant torque. Others learned that the most they paid for a charge was about seven bucks— a lot cheaper than a full tank of gas.

But Newland said the range question is the main drawback for many.

“When the first question ceases to be, ‘how far can you go on a charge,’ electric cars are going to take off,” he said.

For true success, he thinks potential EV owners will need to see charging stations at every gas station. hey will need a range of 300 miles. Five hundred would be better. And finally, the cost of a new EV needs to come down. He knows that will happen. New technology is always expensive, but eventually the price comes down.

Smith is also convinced that electric cars will eventually take off — just like other inventions throughout history that found plenty of skeptics. Heck, Horatio may never have made history if he didn’t bet against those naysayers more than 100 years ago.

“It’s going to start as this trickle,” he said. “And then it’s going to be like a fire hydrant.”

Read: Leading the Charge: Electric Motors Give New Life to Classics